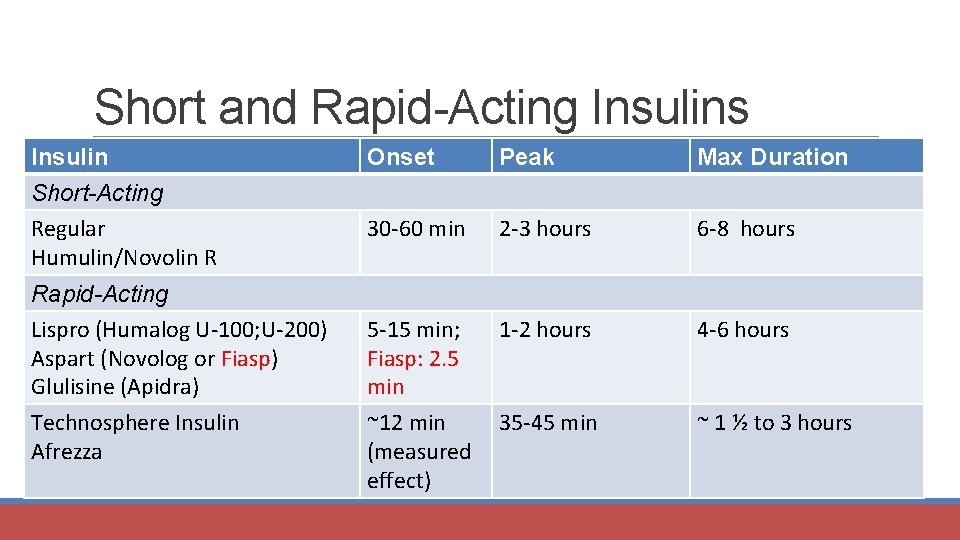

Short-acting insulins have a rapid onset and a short duration of action.

There are three different types of rapid-acting insulin:

- Insulin aspart (Fiasp, NovoRapid, and Trurapi)

- Insulin glulisine (Apidra)

- Insulin lispro (Admelog, Humalog, and Lyumjev)

The average time of onset for these insulins is 15 minutes, except for ultra-fast-acting insulins like Fiasp, which have an onset of action of 5 minutes and can be administered post-meal, depending on the calorie intake. The duration of action for short-acting insulin is about 5 hours.

The dose of short-acting insulin is highly dependent on several factors, including calorie intake, baseline blood sugar level, activity level, and metabolic status. It must be adjusted based on the anticipated rise in blood sugar after a meal and the postprandial blood sugar level.

It is important to discuss the need for multiple blood sugar checks throughout the day. Ideally, blood sugar should be monitored pre-meal and postprandially before every meal. However, this may not always be practical, so checking blood sugar levels for different meals on different days can be an alternative approach. It’s crucial that there are no drastic changes in activity level or diet while monitoring blood sugar. If there is any change in diet or activity level, that blood sugar reading should be considered separately.

For example, if the postprandial blood sugar on an average day (with average food intake, baseline sugar, activity level, and metabolic status) is 220 mg/dL, and we know that 2 units of insulin lower blood sugar by 50 mg/dL, and our target is to achieve 150 mg/dL, we would add 2 units of fast-acting insulin just before the meal.

Blood sugar levels can be adjusted for each meal on consecutive days. It is essential to monitor blood sugar levels regularly and adjust as needed.

We must remember to proceed cautiously, especially before dinner, when controlling blood sugar levels.

Let’s consider another example of initiating insulin therapy.

The patient is a 16-year-old female with type 1 diabetes. She has a history of hypothyroidism and celiac disease, which are common in individuals with type 1 diabetes due to the prevalence of autoimmune diseases. She is lean and thin, showing signs of malnutrition, likely due to being in a catabolic state.

Her blood sugar levels are as follows: fasting blood sugar is 376 mg/dl, postprandial blood sugar is 567 mg/dl, and HbA1c is 14%. Urinalysis shows 3+ glucose and 1+ ketone bodies.

We immediately start by supplementing her with long-acting insulin (glargine). We calculate her ongoing requirement by assessing her excess fasting blood sugar:

- Excess fasting blood sugar: 376 – 120 = 256 mg/dl.

- Insulin needed to manage 256 mg/dl: 256/25 = approximately 10 units (1 unit of insulin typically lowers blood sugar by 25 mg/dl).

We start insulin glargine once a day at 10 units subcutaneously, knowing that we will need to up-titrate it every 2 days by 2 units until we reach the desired fasting blood sugar level.

The patient is also guided regarding dietary intake and exercise.

After a week, the patient achieves a fasting blood sugar level of 116 mg/dl and a post-breakfast blood sugar level of 343 mg/dl at 22 units of insulin. Due to basal insulin requirements and glucotoxicity, a much higher amount of insulin is required compared to our initial calculations. The patient is feeling much better. Now, we need to focus on postprandial blood sugar levels.

We instruct the patient to start using Actrapid insulin, to be administered 5 minutes before meals according to a sliding scale. For a postprandial sugar level of 343 mg/dl (which we initially aim to bring down to the range of 170-180 mg/dl), we calculate the insulin dose required as follows:

- 343 – 180 = 163 mg/dl.

- Insulin needed for 163 mg/dl: 163/25 = 6.52 units.

Let’s start with 7 units of insulin and gradually titrate the dose as needed.

We need to calculate insulin doses for each meal, so we will have to monitor fasting and postprandial blood sugar levels before and after each meal. We follow the same method for lunch. If the pre-lunch sugar level is significantly raised beyond 150 mg/dl, we can increase the dose of short-acting insulin given before breakfast accordingly. If the post-lunch sugar level is significantly increased, we adjust the pre-lunch short-acting insulin dose accordingly.

We apply the same approach for dinner, adjusting the pre-lunch insulin dose if the pre-dinner sugar level is raised and increasing the pre-dinner insulin dose if the post-dinner sugar level is significantly elevated.

The most important aspect is to continuously monitor and titrate the insulin levels. Ideally, blood sugar should be checked 7 times a day (morning fasting, pre- and post-breakfast, pre- and post-lunch, and pre- and post-dinner). Since it is impractical for a patient to check their blood sugar so many times a day, we ask the patient to check their blood sugar for different meals on alternate days. For example, they could monitor breakfast on the first day. Once we have reached a steady state for breakfast, we move to monitoring lunch, and then dinner, continuing to alternate.